|

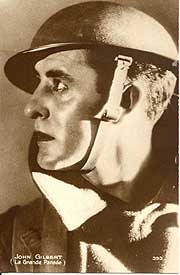

Gilbert

in The Big Parade, 1925

Gilbert

in The Big Parade, 1925 |

Small

At

six he’s big, he thinks, too big,

though normal for a child his age:

he

sees others like him in the streets,

running, playing stickball and hopscotch.

But he’s different. Homes, he ponders

as he watches them in their youthful

exuberance. Those children have homes,

and

I don’t have a home. Well,

he does have a home: Ida, his mother,

left him here; she often leaves him

for months, with people she hardly knows.

So now he sits on the stoop of this hard

rat-laced brownstone in this hard

New York Irish neighborhood in

the hard summer of 1905. Sweating

in the sodden heat he looks out

across the faces, the horses, the motorcars

in the street, his knickers dirty, spotted

with oil and grime and drops of urine.

They have homes, he thinks again,

sounding the words in his mind

as if they were poetry. He remembers

the dark backstages of a dozen cities,

learning words from the dog-eared scripts

left on sawdusty floors, hearing Ida spit:

Every minute the little bastard gets bigger

is a minute I’m getting older. Big, big!

He stares at the children in their dresses

and hats, imagines willing himself

smaller, smaller still, so small that

the seamstress he’s been left with

will stop yelling, stop telling him

she only has one room for God’s sake,

what does he think visitors make of him

staring moony-eyed from the corner?

(One

after another, four or five

a night sometimes, he’s left alone

for hours and then the door clicks,

rattles, bursts open to her heavy

melodious trilling. Here we are, love,

she’ll say, skeletal worm-pale woman

with bristles in her chin. He won’t

be introduced. Forget him, he ain’t

nothin’. The lights will go black

as the two of them drop onto the bed.

Sighs; creakings; a whispered Jesus

or Yes or Shit as he sits on blankets

in the corner, eyes shut tight,

fingers pressed into his ears, willing himself

away, projecting himself onto a stage

in a vast auditorium, grinning brilliantly

in flowing tuxedo and elegant tails,

applause engulfing him in warm waves,

his mother queenly in a vast frill-filled dress

and tiara, gazing adoringly up at him,

proud of him, so proud, loving him

at last, and taking him finally in her arms

and whispering, My love, it’s time to go home.)

Yes, he thinks, staring at the grime-caked

street before him, at the ice vendors and milk

wagons, at the men strolling with their cigars

and the women with their laundry baskets, if only

he could make himself small, small enough,

smaller than a dog, than a gerbil,

smaller than a baseball, she would take him

back, drop him gently into her soft pocket

where the jostling warmth would hold him

safe always. And he can do it, he’s sure,

if he tries, if he concentrates, if he puts

all his might into the attempt, and he shuts

his eyes, shuts out the shoutings and cabbage

smells of the street, tries to dissolve himself,

to shrink, expecting when he looks again

to find himself no bigger than a puppet,

or a toy soldier, or a picture in a nickelodeon:

tiny, perfect, worthy at last of home.

TOP OF PAGE

Gilbert and Garbo in Love, 1927 |

White

Dark

The

streets of Stockholm swirl

with snow, white on white so intense

that it seems to devour the dark itself,

make blinding noon at midnight.

Keta has separated from her

brother and sister, found her way

into an alley off G`tegatan,

where she hears shouting voices—

she wants to go home, but everyone

in the neighborhood knows

about the Gustafssons, Anna and Karl,

Karl the butcher who comes home

smelling of blood and brain, Anna

who can match him blow for blow,

and how the children, Sven, Alva,

and little Greta whom they call Keta escape

out the back door into the white city dark.

Sometimes neighbors take them in,

coo over them, beautiful little Keta

especially, with her huge lovely eyes

and serious ways. Keta has heard

of a place called America, where the sun

always shines in a sky always blue,

where people ride in motorcars like chariots,

where the flickers, which she, six years old

in 1911, has never seen, project faces

forty feet high that live forever. But

all that is dreamtime. Now there’s only

the alley, two drunks trying to fight

while half a dozen men cheer them on.

Blood drains from the smaller man’s

nose. She watches, remembering blood

from her mother’s nose, the doctor

in the middle of the night, his serious

words to Papi: You really must not

treat the mother of your children

this way, it’s not right, you know.

Karl humble, regretful, as he would

always be, later, tears flying down

his face, grabbing at Keta, his favorite,

hugging her close. The snow

drops everywhere, on the fighting men,

the street, the ashcans, Keta’s hair

and eyelashes. Snow, snow.

The smaller man falls and suddenly Keta

has pushed through the grownups, crying,

Stop! Stop! Can’t you see he’s beaten?

And, kneeling down, holding the man’s

head, so like that of her father,

the same unfocused eyes and boozy stench,

she cradles it as she does her father’s,

using the hem of her dress to wipe the blood

from his face, blood mixing with snow

in her dress as she whispers, again

and again, like a mantra she’ll chant

all her life: Beaten, beaten, beaten.

TOP OF PAGE

Charity

Ward

Twelve

years old, thirteen, she takes her father

each week to the charity ward, blue water-streaked

walls, broken chairs, sits him down among

shadow-eyed prostitutes, rickety tuberculars.

He’s made an effort this time, isn’t drunk.

"Sober as a stone," he’d said proudly that morning,

to any in his family who would listen. Only Keta

did. He’s convinced that what’s wrong with him

won’t be wrong with him if he’s sober—after all,

it’s the brannvin that’s causing it, isn’t that

what the doctor said? Keta remains with him

during the exam, even when she’s asked

to leave: "No, she stays with me," he declares.

He strips off his shirt, exposes his pallid, lumpy

body, the doctor taps his back, listens to his heart.

"Karl," he says confidentially, leaning close to him

as if he wishes Keta not to hear, "you simply must

stop drinking. Don’t you know that?" Her father

nods humbly, thanks the white-coated man, puts on

his shirt and tattered Homburg hat. "I stopped

already," he says to her on the way home, suddenly,

indignantly. "Doesn’t he know that? Sober as a stone,

as a stone. Keta," he says finally, "you go on

home, yes? Papi has people he needs to see."

She obeys, always, always obeys, kisses him

on his stubbly cheek, says so long, Papi,

be well, moves up G`tegaten toward the slums

and home, glancing back only once

to see him chatting with friends, tipping

his head back, flask to his lips: happy, she thinks,

as a boy, a boy finishing a race, or a test, or a boy

helping his girl up the steps to the abortionist’s office.

TOP OF PAGE

Camera

Sixteen

and he’s the damn fool

grinning into the camera as he

gallops past on a white steed,

one of thirty-eight Yankees.

Later he’ll slip into a Rebel’s uniform,

charge back the other way;

spliced, the thirty-eight of them

will ambush themselves. Such

madness! Such fun! He loves

to sneak into the rushes, gaze up

at the glowing images as they

careen forward and back, are

slowed, stopped, started again,

and he glimpses himself now and then,

bright white face in a white sea.

But this day he sinks into his seat,

lowers his cap over his eyes as

the producer waves his cigar

at the screen and screams,

Who’s that idiot looking

into the camera? They stop

the picture, slowly reverse it,

thread one frame at a time through

the projector until, yes, there he is,

Jack Gilbert, caroming by in a blur

but not quite a blur, his head turned

straight to the camera, grin gleaming

out to the world. Fire that son

of a bitch! the producer bellows,

gesticulating wildly, and an underling

assures him it will be done, sir. But

the next day Jack reports to work

as usual, attacks himself as usual,

whoops and roars with the rest

and, every now and then,

steals a secret rascal’s glance

straight into the camera’s eye.

TOP OF PAGE

America

A

few films and she’s famous, a little,

in her little country, she and The Director.

But this is nothing, he scoffs: Peasants!

Farmers! Garbage-eaters! America,

America it must be, and soon is:

goodbyes at the dock, Greta weeping

into her mother’s bosom, The Director

checking his watch again and again.

They sleep chastely, in different cabins,

despite her pleas that they stay together,

not for any indecent reasons, God no,

but just for company, companionship.

Stupid little schoolgirl, he mutters,

slamming his door in her face.

She’ll

wander the deck for hours

at night, breathing the sea-spray,

imagining dropping away into space,

splashing down through the depths

to live with sharks and squid.

When she sleeps at last

the ship will be a mausoleum,

her dark cabin a coffin, and in the morning

he’ll kill her, obliterate her with

a few words and sheets of paper:

You

must forget Keta Gustafsson.

Think of her as dead. And so she becomes

someone new, newly named. Alone, she’ll try

the syllables on her tongue: Gar. Bo. Gar-bo.

Greta Garbo, she thinks, heading

to America: to paradise, to greatness,

part bright star, part shambling corpse.

TOP OF PAGE

Joan Crawford and Gilbert in Twelve Miles Out, 1927 |

The

Studio Lot at Midnight

Arms

interlocked, the silence between them warm

and content, there’s no other place they can even imagine

wanting to be. How real, this: Dodge City or Amazon jungle,

Paris or darkest Africa, all empty, uninhabited worlds

entirely theirs to share, without agents or makeup men

or producers or fans jostling them on the street cadging

an autograph, a touch, a buck from Gilbert or Garbo who seem,

sometimes, to themselves, less real than dreams; roles,

put-ons that others animate, keep alive, love, try

to tear down. Here, now, nothing is wanted of them

by anyone. They live, for a few minutes at least, only

for each other. Their shoes scuff softly through the dark

interstices, worlds between worlds, neither of them in any

hurry to reach Athens or Rome, happy to pause in Bethlehem

or even Hollywood, to share a cigarette, a word, a slow kiss,

their only abiding company the patient and radiant stars.

TOP OF PAGE

Movie photos courtesy

of http://www.johngilbert.org/

The John Gilbert Appreciation Society.

|