|

The

Wedding

Her

dress is perfect.

Her ring is perfect.

Her husband is perfect.

The families are perfect,

the laughter and cheers and toasts,

and they dance for hours,

she careens this way and that,

high on champagne

and wild reckless love,

and, later, she'll think joyfully

that this was the best day of her life,

and, later, she'll think mournfully

that this was the best day of her life.

|

|

|

TOP

OF PAGE

The

Silence

Like weeds

they seem

to sprout, his wife's ideas,

her lecturing him, which began

hesitantly, but lately

grows to shrillness about

God's children and

abominable practices and

the rights of man, and

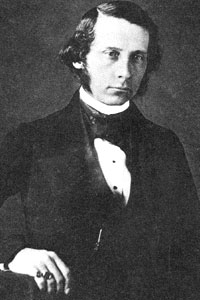

Pierce Butler of America

has never heard such words

from the mouth of a woman, and

it's shocking, this pathetic

attempt of the female mind

to grasp what is so patently

beyond it, and he tries to be

calm, to placate her, divert

her attentions to pretty things

more suited to her sex. She'll

have none of it, angry words

flying from Fanny the righteous,

Fanny the pure of heart,

until one evening, exasperated

beyond human endurance,

he makes the simple point,

in simple, polite language, that

as his wife she is herself

one of the largest slaveowners

in the state of Georgia, and this,

at last, silences her, leaves her eyes

wide and throat pulsing, and though

he knows he shouldn't, he

allows himself a small sense

of victory when he walks past

her room later, hears the weeping

on the other side of the closed door.

TOP

OF PAGE

Learning

the Language

As a boy

Jack would use many words,

and sometimes they earned him

a harsh rebuke in return, a slap across

the face, the lash itself over his back

and shoulders, and so he learned to speak,

to remove the bad and stupid language

like why and stop and wrong

and replace it with just one word, a word

that was always the right word,

and so to the Major he says Yes,

and to the Missis he says Yes,

and to their children he says Yes,

and to the overseer he says Yes,

and to every white person he sees

on God's Earth he says Yes, and it's

a beautiful and harmonious world

of Yes which he says again and again,

even in his sleep, to smother the No

that lurks always at the base

of his spine, hot, acidic, ready to spring.

TOP

OF PAGE

Triumph:

A Definition

Over crabs

and wine, their friend Sidney George Fisher

tells Fanny of a master he'd known in Alabama

who'd dressed a favorite slave up in motley,

cap-and-bells, red pantaloons, and paraded him about

wherever he went, pulled along by a leash and

rhinestone-studded collar. This slave, Obediah by name,

would sing, dance with considerable agility, and perform

simple magic tricks, for which he would be rewarded

with small candies which the master kept in his pocket

and which Obediah would catch from mid-air in his mouth.

When Fanny comments about the sorry humiliation of

it all, Fisher tells her, looking thoughtfully through the window

at the glistening blacks in the ricefields down the hill,

that Obediah, who never lived a day out of the collar

until his last years, sired fourteen sons, celebrated countless

grand- and great-grandchildren, and died at the age

of ninety-six, in a featherbed big enough for three.

TOP

OF PAGE

|

|

|

Hearing

Stories

She

wants to hear it, hear it all,

and so Jack tells it, tells it all,

about Glasgow's whipping, the tying

his arms around the old oak, his feet

left on tiptoes, just touching the ground,

and the overseer's fat leather strap,

how the wounds opened after three

strokes, how you could see blood

spattering from the lash after five,

and his screaming...She says to go on,

go on, Jack, and he tells her how they

all watched and listened, the overseer's

arms pumping regularly as a cotton gin,

as Glasgow's screaming faded to

gasping, then croaking, then nothing,

and his eyes rolled back in his head,

and that was all...And she says to go on,

go on, Jack, and he tells her how

they untied the carcass then, how

the overseer raised a rusty can

over Glasgow, opened it, poured

rock salt over the blood-drenched

wounds and demanded that House Molly

get down on her knees, rub the salt in

good and strong, and as she did it he

came awake, oh! yes, a wet moan

rattling in his throat...And she says to go on,

go on, Jack, and he starts to laugh,

he can't help himself, he laughs,

looking at the pretty white lady next to him

in the boat, at her intently glistening eyes

and sweat-soaked white skin,

and she asks him, suddenly, through

his merriment, Jack, why are you laughing?

and he can hardly gasp an answer, which

isn't the right answer, as he says,

I don't know, Missis, I guess there was

just somethin' funny about it, and she

studies him curiously, tensely,

as she says, suddenly, like

a thunderbolt in a clear sky, Jack, tell me

the truth, would you like to be free?

He stops laughing then, stops completely,

and there is a silence between them-until

he explodes again, great whoops and guffaws,

and the whole world is funny to him at that

moment, the boat, the river, the white lady,

poor bloody Glasgow, and the question,

the funniest of all, hilarious, breathtaking!

|

TOP

OF PAGE

Patrimony

Once, as

she writes in her room by dim candlelight,

she glances up and sees Sarah in the doorway, smiles

and calls her Bumpkins, as she always does, invites her

in, but the figure doesn't move, says only, Missis?

And, looking again, she realizes that it's a slavegirl

named Josephine, not Sarah at all, yet for a slanting instant

she'd been sure, positive, and as she looks now

she sees something she's never, somehow, quite seen,

that Josephine does look rather like an evening-hued

molding of Sarah, Sarah with her high cheekbones

and round dark eyes, Sarah who has always been

the mirror's very image of Pierce Butler, her father.

TOP

OF PAGE

|